Holy Nepsis

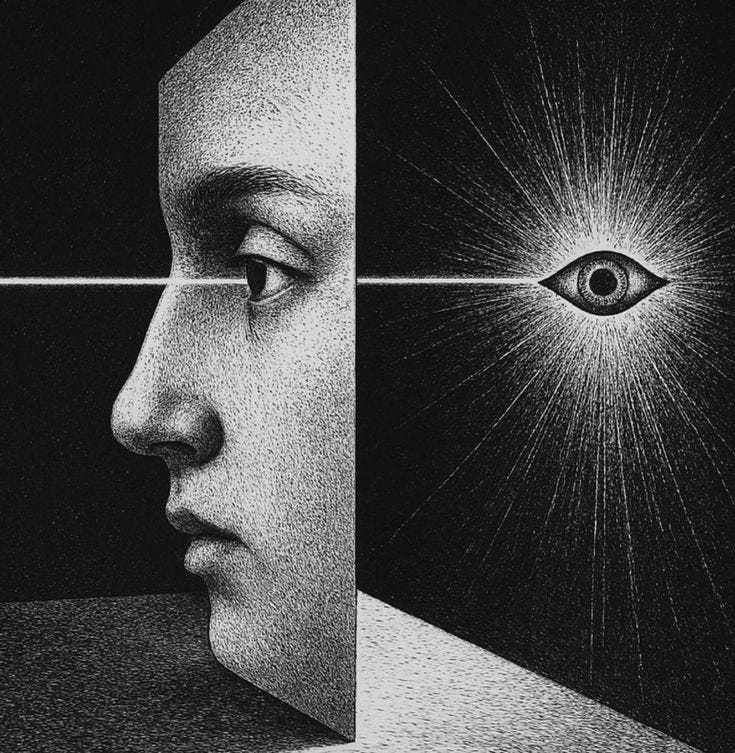

Observing the Observer

There exists a certain practice within the Eastern Christian mystical community called nepsis. In the spiritual text known as the Philokalia, several spiritual writers assert this practice as paramount in the process of theosis, analyzing its form, advising its practice, and warning the practitioner of the various obstacles one might encounter along the neptic journey.

Nepsis is described as an inner watchfulness of the heart, ordered toward filtering thoughts which arise in the mind so that sinful thoughts do not enter the heart. Now, entering the heart is clearly mystical language, but what these authors mean by this is giving conscious consent to the thoughts that arise. Thoughts enter the heart only insofar as they are willfully accepted by the nous. The nous is the faculty most closely translated as mind; however, this definition is admittedly fast and loose.

For the Philokalic writers, and for much of Greek thought more broadly, the nous is the innermost core of the psyche or soul. It is intended to be the highest faculty of the human person. The nous is the most fundamental psychic organ of perception, one not confined to awareness of sensory stimulation, but capable of transcending it in pre-linguistic awareness. Thus, the nous is presented as the hegemonikon, the ruling faculty of the soul.

To engage in holy nepsis, one does not simply attend to individual thoughts, but rather transcends the purely biological mind and becomes consciously aware of the entire psychic ecosystem. This is not transcendence in the Advaitic sense, but rather a movement by which the nous observes the activity of the psyche, including its own operation. It is responsible for awareness itself. Nepsis, in its purest sense, is the act of operating awareness from the faculty of the nous. The fathers explain that in order to do this, one must descend into the heart. Again, this is mystical language—so what exactly does it mean?

To descend into the heart, one attempts to quiet the mind of discursive thought. For example, when attempting to achieve inner stillness or nepsis, one may observe a thought such as, “I still need to go to the grocery store later today.” The awareness of this thought does not itself break inner silence; engagement with it does.

If one becomes aware of the thought and consents to it—allowing it to enter the heart—one immediately enters into communication with it and may respond internally: “I’ll go right after I’m done practicing inner stillness,” or “That reminds me, I’m out of Cool Ranch Doritos,” followed by a cascade of preference, memory, and association. Very quickly, the core of our being—our awareness—is captured by reactive states influenced by the material world.

To remain in a neptic state, however, no response is given at the first awareness of the thought. It is simply observed, while attention remains fixed not on the content of the thought, but on the level from which awareness itself is exercised. In this way, the thought passes without commandeering the inner life. One might reasonably ask: what is the practical value of this?

The practical value is that nepsis reveals a diagnostic state of the soul. Awareness precedes emotion, thought, and every other form of stimulation. For any stimulus to become affective, it must stimulate something. Yet in modern life we are constantly bombarded by sensation and thought in rapid succession—so much so that we bypass the nous altogether and begin responding to reality in a manner closer to instinct than rationality. We experience a thought and immediately identify ourselves with it.

The English language itself reveals this condition. When someone is hungry, they say, “I am hungry.” When they are sad, they say, “I am sad.” Notice what occurs here: self-identification becomes synonymous with transient inner states. We unconsciously begin to identify our very being with our thoughts and emotions.

What nepsis reveals is that we are not our thoughts; we are the capacity for awareness of those thoughts and for engagement with them. Through this process, one begins to realize that one is not obliged to instantly acquiesce to every internal movement. We are no longer slaves to internal conditions. Desire itself begins to shift—from what is purely external and reactive toward what is interior and ordered.

At this point, someone familiar with other mystical traditions may object: “Isn’t this exactly what Buddhists or Hindus practice?” In a structural sense, they would be correct. We are all working with the same interior material. The distinction, however, lies in the object and the ontological direction of the practice.

For the Philokalic tradition, nepsis is not important merely because it increases agency. Its significance is far more profound. As nepsis stabilizes within the psyche, desire subtly shifts—from impulsive attraction to receptive inclination. Desire in a state of inner stillness is no longer something produced by the mind, but something to which the core of one’s being aligns itself—something primordial, something transcendent. It is no longer received from the world, but encountered through a newly purified interior disposition. Silence, then, does not become emptiness. It becomes fullness, as distraction and impurity are gradually burned away.

In the neptic state, willing no longer appears as a battle against resistance, but as a fluid movement of the self. Action becomes assent rather than assertion. This represents an ontological shift in which the will no longer competes with reality, but cooperates with it. The fathers describe this not as a loss of freedom, but as its fulfillment.

This participatory mode of being is known phenomenologically before it is conceptualized, and enacted practically before it is articulated. Nepsis trains the person to act in accordance with the intelligibility that already orders reality. Ontology ceases to be something merely contemplated and becomes something lived. Being is no longer approached as an object of thought, but as a mode of participation.

The higher movement experienced within nepsis does not present itself as an external command, but as clarity without compulsion. One is not dominated by reality; rather, the will begins to flow with it in synergy. This carefully distinguishes nepsis from psychological determinism, mystical passivity, and absorptive non-duality. The self is not dissolved, but restored.

Other traditions may aim primarily to quiet the mind. Christian asceticism seeks to transfigure it. The goal is not the destruction of desire, but its healing; not the negation of the will, but its proper ordering. Nepsis thus serves as a practical doorway into participatory ontology. It does not begin with a list of theological facts, but with lived experience. It reveals that participation in the One is not an external act, but an interior disposition—one that changes not what we do, but where our doing comes from.